I’ve done something some of you might find appalling, others boring, a few amusing, and perhaps some will see it as indulgent—or even as an excuse not to hate what they hate.

I’ve listened. I’ve watched. I’ve followed politics—and grown tired of the language we keep using.

“He’s a leftist.”

“She’s a fascist.”

Same old drivel. The same tired labels thrown around whenever people try to describe modern problems.

This frustration has been building in me for years: first as a participant in activism, then working in a union. Through the Iraq war, the banking collapse, Brexit, Trump’s two elections, Putin’s reimagining of Russia, and Xi Jinping’s disruption of the global order.

I’ve watched intelligent people dismiss anyone who deviates even slightly from the opinions they hold dear—writing them off as products of their upbringing, education, or social class.

And always the same words: Left. Right. Centre. Left of centre. Right of centre. They’ve become meaningless.

So, I locked myself away. I analysed the way we talk, the things we fight over, and I built a new perspective. A new framework. A way to measure the world around us differently.

That work has become my next book, The Governance Paradigm, which I’ll be releasing in the new year.

The premise is simple: politics changed thirty years ago, when the Cold War ended. Ideology no longer defines the battlefield as it once did. Instead, we live in the age of governance and systems—where our greatest conflicts emerge. And layered through it all is a powerful lens that we all feel passionately about: our identity.

A New Compass

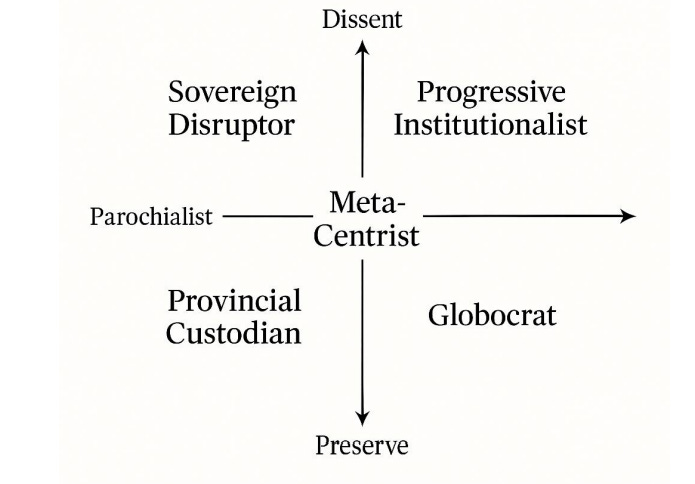

Politics no longer makes sense when squeezed into “left” and “right.” We need a new map, one built on two questions:

Do you see the world through local, rooted identities (Parochialist) or global, interconnected ones (Cosmopolitan)?

Do you want to preserve today’s systems and institutions (Preserve) or challenge and dissent from them (Dissent)?

Together, these axes create five archetypes: Sovereign Disruptors, Provincial Custodians, Globocrats, Progressive Institutionalists, and a redefined Centre.

Systems: The Y Axis

We live in an age of intricate systems—governments, courts, markets, treaties, and bureaucracies. I call this the Consentīre, from the Latin “to agree together.”

Preserve: These frameworks, though imperfect, are the best way to safeguard progress.

Dissent: The system is corrupt, outdated, or unjust—and must be challenged or reimagined.

Identity: The X Axis

The second axis is about identity.

Parochialist: Rooted in heritage, faith, and belonging.

Cosmopolitan: Rooted in universal rights and shared humanity.

This is the gravitational pull of politics: whether we define ourselves through inherited communities or global connections.

Beneath the Axes

These axes aren’t just abstract lines. Each one is grounded in real-world factors.

The System axis touches on legitimacy, governance, political voice, and economics.

The Identity axis is shaped by memory, culture, justice, and even questions of sex and gender.

Together, these threads give the compass its depth—turning it from a sketch into a tool for analysing people, movements, and nations.

Why It Matters

When these two axes meet, they form the archetypes of our age:

Sovereign Disruptor (Parochialist + Dissent) – defending local identity by disrupting systems.

Provincial Custodian (Parochialist + Preserve) – protecting tradition while upholding institutions.

Globocrat (Cosmopolitan + Preserve) – global cooperation through treaties and markets.

Progressive Institutionalist (Cosmopolitan + Dissent) – reforming systems in the name of universal values.

Centrist (varied) – shifting “middles” that stabilise, bridge, or cluster politics.

Questions Worth Asking

Here’s where it gets interesting. Instead of slotting yourself into “left” or “right,” ask yourself:

Do I define myself more by who I belong to—or by how I am governed?

When I clash with others politically, is it really about identity, or about the system?

Do I feel more loyalty to my community and heritage, to a wider, universal global community, or to the institutions that govern me?

When the system fails, do I want to reform it—or replace it?

The Point

Politics today doesn’t map neatly onto “left” and “right.” That old compass is obsolete.

The Governance Paradigm is my attempt to sketch a better one.

The book will be out in the new year. If you want to follow along as I share more case studies and ideas, hit subscribe

And if one of those questions unsettled you—tell me in the comments which one, and why.